He is presently the president of the Biennale di Venezia.

Paolo Baratta received his degree in engineering from the Polytechnic University of Milan in 1963, and received his B.A. degree in economy from Cambridge University (UK) in 1965.

After returning to Italy, Prof. Pasquale Saraceno proposed he collaborate at SVIMEZ, the research facility founded in 1947 which studies development economics, with a focus on development in Southern Italy. There, he conducted research in the field of development economics, with frequent interchanges with the industrial world, IRI, his own research facility and those of major Italian companies, and government authorities. [1]

Although he has never pursued a career in politics, Paolo Baratta has always leaned toward reformism.

During that period, he worked on various papers which were published in numerous journals and he collaborated on writing the sections dedicated to industry in the annual Rapporto Svimez He also published the books Gli investimenti industriali nel Mezzogiorno in collaboration with Mario Amendola (Giuffrè 1978) and Prospettive dell’economia italiana with Lucio Izzo, Antonio Pedone, Alessandro Roncaglia, and Paolo Sylos Labini (Laterza 1978).

Today, Paolo Baratta is a member of the Italian Society of Economists.

Starting in 1978, Paolo Baratta was first a board member – representing Cassa Depositi e Prestiti – and then vice-president of Crediop-Icipu. In 1980, he was named president of the two institutions by the Treasury Minister, Filippo M. Pandolfi [3], with the concurrence of the Bank of Italy; this position was reconfirmed in 1985 [4].

The period 1978-1981 was very complex in Italy’s public life, and in particular, its banking system.

Crediop and Icipu, “twin” public credit institutes for medium-term credit, were founded by Alberto Beneduce in 1919 and 1924, respectively: the first to finance public works, the second for public utility companies (its contribution was decisive in providing Italy with basic infrastructures and services, before and after WWII).

The two institutes were in great difficulty because of enormous insolvency and losses on credit granted to highway companies and major chemical groups (Montedison, Liquigas, Sir) [5]. Many meetings were held in those years between the top management of the banking and insurance systems, the Central Bank, and government authorities; eventually, and with difficulty, they were able to define the programs and methods to adopt for reorganization and settlements.

The recapitalization and the merger between the two institutes, plus changes in the statute fostering greater openness toward corporate financing, enabled the recovery and development of the Institute created by the merger.

Starting in 1985, very positive results were achieved in terms of activity and profitability [6][7] and in 1991, Crediop was named one of the most efficient banks in Europe [8].

In the wake of new trends which had matured during that period in the specialization of credit, Banco S. Paolo di Torino became a Crediop stockholder [9].

This action was defined (albeit inaccurately) the first privatization.

Under his presidency, Crediop became a sponsor of the Fondazione Lorenzo Valla for Greek and Latin Classics [14].

During the 1980s, following shareholding acquisitions by the Institute, Baratta became a board member of Olivetti, Zanussi (Electrolux), and Setemer (Ericsson). Crediop also became a shareholder of the Nuovo Banco Ambrosiano. This position proved to be decisive when the syndicate agreement underpinning the Nuovo Banco Ambrosiano found itself in a crisis situation when the Banca Popolare di Milano withdrew and pressure was applied (in particular by Mediobanca) to allow Assicurazioni Generali to step in (instead, Credit Agricole entered). In a particularly tense situation, a public institute – pursuing its own interests – played a decisive role in preserving the autonomy of one private institute from another private body considered an “aggressor” [10].

During the 1980s, Paolo Baratta was vice-president of the Banco Ambrosiano Veneto [11], he declared himself in favor of the separation between banks and financial institutions [12] and signed the manifesto for the single European currency [13].

For a number of years, he was vice-president of the ABI (Italian Banking Association), as well as president of the Centro Alberto Beneduce for economic and banking studies, which concentrated primarily on the “German model,” new problems in regulating “international payments,” and the growing volume of financial transactions.

After his ministerial experience, Baratta returned to the banking sector as president of the Italian branch of Banker’s Trust. After 2007, for several years he was an independent board member of Telecom S.p.A. (where he was also president of the control and governance committee), of Ferrovie dello Stato S.p.A., and of Edizione Holding S.p.A.

During these years, Paolo Baratta published numerous papers on the origin and problems of medium-term credit, the specialization of credit, the origin of state holdings, the rise of special institutes in Italy, the Central Bank, and works on Stringher, Beneduce, and Menichella.

In 1993, during a particularly complex moment in Italy’s political life, Prime Minister Giuliano Amato called on Paolo Baratta to join the government as a technical minister with the role of Minister for Privatizations [15].

In this role, he had to take immediate action to alleviate critical situations which, to varying degrees, were affecting the system of state-held enterprises within the new framework which emerged when management entities were transformed into limited companies (a law from 1992): structural crises which had not improved after the devaluation of the lira, and local crises which had been sparked when investment programs were interrupted or plants were closed.

Tangentopoli raged.

In that period, Baratta presented the Council of Ministers with the first measure to institute Regulatory Authorities for companies which manage public services [20]. The next government would return to this topic with a definitive measure.

In this short period of time, he concentrated primarily on the crisis in the iron and steel industry [16] and concluded agreements to find a solution for areas affected when lead and zinc mines were closed in Sardinia [17], he participated in union agreements with Alenia during a moment of deep crisis in the aeronautic industry [18], and he fine-tuned the CIPE resolution regarding telecommunications [19], introducing for the first time the need to separate the manufacturing and services sectors of the STET Group. Launching a policy of privatization raised numerous legal, economic, and social problems.

From 1993 to 1994, Paolo Baratta was called on by the government of President Ciampi to fill the role of Minister for Foreign Commerce. He was then asked to assume ad interim the role of Minister of Industry, as well; in this capacity, he concentrated in particular on the final phases of the international negotiations for the new Commerce Treaty (Uruguay Round) [21]. In February 1994, Baratta, representing Italy, signed the treaty in Marrakesh which established the WTO (World Trade Organization) [22].

During the many meetings of the Council of the European Union, Baratta upheld Italy’s position in favor of lowering trade barriers, in particular against the resistance of Japan and the United States, which defended their high tariffs in strategic sectors for Italian exports, such as footwear and clothing [23].

Taking advantage of an enabling act, Paolo Baratta launched a complete reform of the Ministry of Foreign Trade [24].

It was the first mission by a European country after the events in China which had culminated in Tienanmen Square.

In 1993, Baratta organized a trip to China with a delegation of industry representatives; for the first time, providers of services and infrastructures also participated [25].

Between 1995 and 1996, the Dini government appointed Paolo Baratta, always as a technical minister, to assume both the roles of Minister of Public Works and Minister of the Environment.

As Minister of Public Works, through a regulatory measure (legislative decree n. 101/1995), he reactivated the law governing contracts (the Merloni law, which had been suspended by the previous government) and oversaw the drafting of the first regulation provided for by this law [26]; he launched a decree governing service contracts (law n. 157/1998) and excluded sectors (law n. 158/1995); continued coordinating the works deriving from the liquidation of Agensud (Cassa per il Mezzogiorno); and gave momentum to the activities of the Water Authorities, which had always been considered an example of interventions on the territory. The statute of ANAS (which had been seriously affected by judicial investigations) was reformulated: it was transformed into a government-owned company and an internal technical service was created to evaluate the environmental impact of all its projects.

It was the only time in the history of the Italian Republic that the same person headed the two ministries at the same time.

The year 1995 marked an upswing in public works sites [27].

At the conclusion of the services conference of the new high-speed Florence-Bologna railway, Baratta, in part to foster the conference’s positive outcome, was able to convince all the participating public bodies to sign a private agreement. The objective was to organize permanent oversight and a site for negotiating the reconciliation of possible controversies, before progressing to the administrative authorities [28]. This was something new in Italy’s administrative system, and had positive results as the work was underway.

As Minister of the Environment, he chaired the Council of the European Union during the Italian semester of the EU. During this period, the IPPC Procedure for the authorization of industrial plants was approved.

During Baratta’s mandate, a decree was introduced to limit the presence of benzene in gasoline [33].

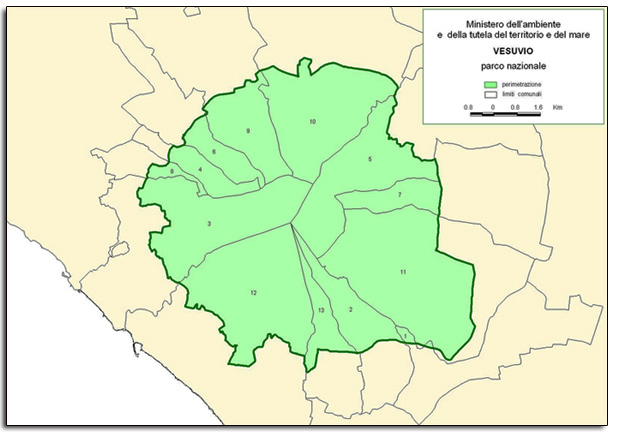

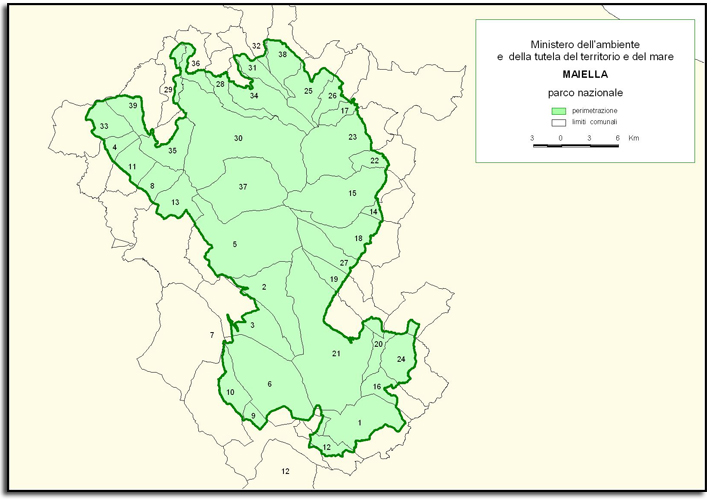

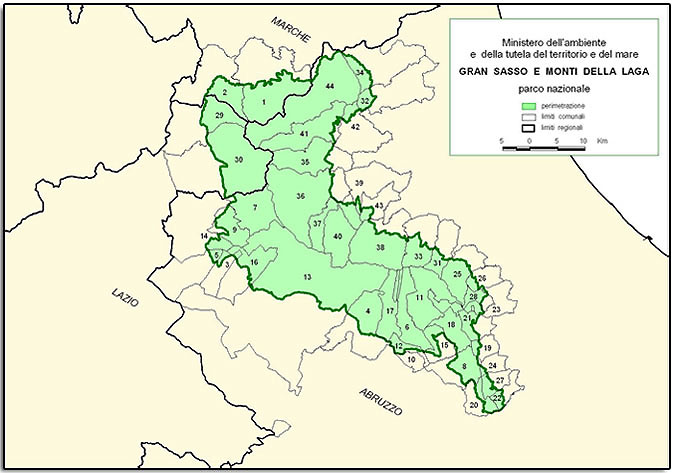

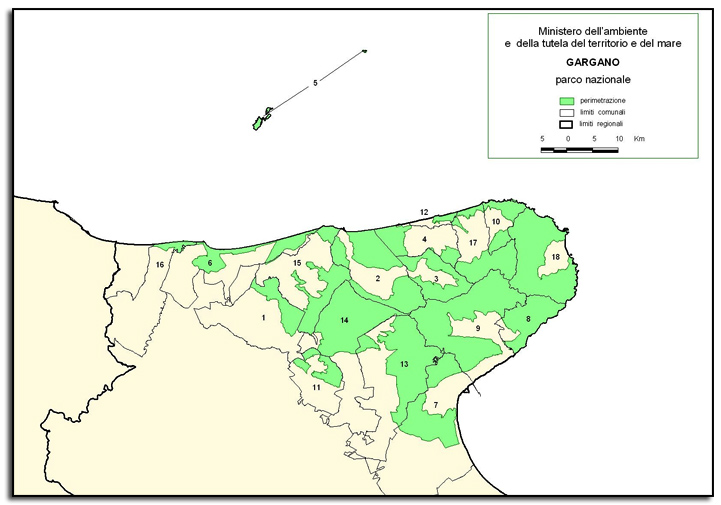

With these acts, the surface area of Italy’s parks more than doubled, to represent approximately 7.8% of the country’s total surface area.

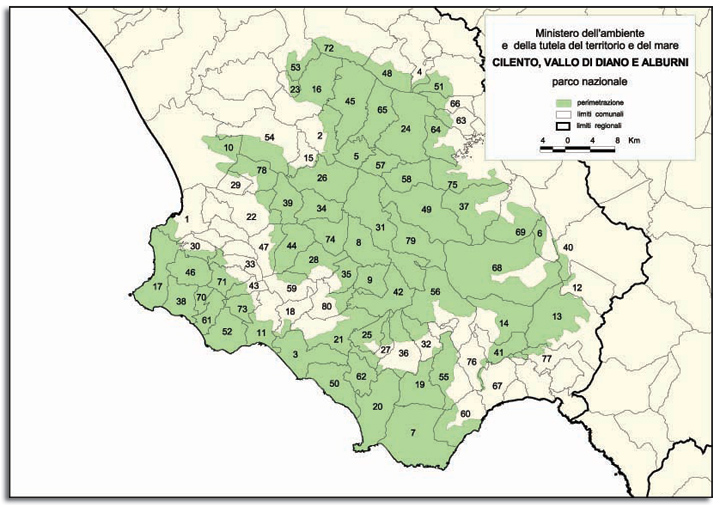

In this capacity, with a decree Baratta finalized the creation of five National Parks (Maiella, Gran Sasso, Cilento, Vesuvio, Gargano, La Maddalena) [29] at the end of the negotiations to define their perimeters: a total surface area of 530,000 hectares. Baratta also signed an agreement with the Region of Sardinia for the Gennargentu National Park.

In this dual capacity, Baratta chaired the ministerial committee for the safeguarding of Venice and its lagoon, and launched the creation of an international commission of experts to further evaluate the environmental impact and put a limit to the transit of oil tankers in the Venetian lagoon [32].

In March 1998, Paolo Baratta was called on to chair the Biennale di Venezia [34]. The nomination arrived just after the approval of an important reform law to update the legal nature of the Biennale (making it liable to civil law) and its organization (work relationships regulated by private collective contracts), and to reduce the number of members of the board of directors from nineteen to five.

1999 also marked the beginning of annual or biannual activity in the other sectors, which were assigned new spaces.

First of all, new, clearly dedicated spaces were necessary in order to obtain enough room for the international exhibition “open” to the world: an extensive renewal of the areas already in use was begun. A vast portion of Venice’s Arsenale (of which only a portion had been used by previous exhibitions) was obtained, initially for use and then in concession, from the administration of the civilian and military State Property Office; a program to restore and restructure the area was then begun to create vast exhibition spaces. A theatrical area dedicated to dance, music, and theatre was created; until that moment, the Biennale had lacked a similar area.

This reform also affirmed the institution’s high level of autonomy in the formulation of its orientation and decisions. Up until then, the Biennale had been a semi-public body; it had recently weathered a complex period of instability and structural difficulties; its organization had to be innovated, as did its orientation and programs.

The Art Exhibition’s traditional model, organized along national pavilions, evolved in a definitive and permanent manner into a model resting on two pillars: a general international exhibition open to the entire world, with a curator named by the Biennale; and a complex of national pavilions governed by a commissioner and a curator.

The new breadth, stability, and clear organizational structure of the Art Exhibition, as well as the improvement in its available space, fostered an increase in the number of participating countries (from 59 to 86) and visitors (from less than 200,000 to 620,000) between 1999 and 2017, all the while without conducting any promotional activities in the countries themselves, or undertaking any advertisement commitments.

In 2001, Paolo Baratta resigned his presidency a few months before its scheduled termination .

In 2007, he was called back to the presidency of the Biennale for the four-year period 2008-2011 (in 2011, a local newspaper launched an international petition for his confirmation which received 4,500 signatures), and was confirmed once again in 2011 (for the four-year period 2012-2015) and in 2015 (for the four-year period 2016-2019).

After renewing the Art Exhibition, particular thrust was given to the Architecture Exhibition, which in recent years has affirmed itself as the most important appointment in the sector worldwide. Restoration was completed of the Historical Archive, whose collections today are valorized by exhibits and various initiatives. The new Library (2010) was built. The Arsenale was reconverted through further major restoration work (in the Sale d’Armi, for example) which was conducted with contributions from participating countries. The presence of a large Italy Pavilion was consolidated in the Arsenale.

Curators and artistic directors of La Biennale nominated under his presidency and proposed by Paolo Baratta

1999-2001

Harald Szeeman for Art, Massimiliano Fuksas and then Deyan Sudjic for Architecture, Carolyn Carlson for Dance, Michele Dall’Ongaro and Bruno Canino for Music, Giorgio Barberio Corsetti for Theater, Alberto Barbera for Cinema.

2007-2011

Daniel Birnbaum e Bice Curiger for Art, Aaron Betsky and Kazuyo Sejima for Architecture, Marco Mueller for Cinema, Maurizio Scaparro and then Alex Rigola for Theater, Luca Francesconi for Music, Ismael Ivo for Dance.

2012-2015

David Chipperfield and then Rem Koolhaas for Architecture, Massimiliano Gioni and Okwui Enwezor for Art; Ivan Fedele for Music and, after one more year to Ismael Ivo, Virgilio Sieni for Dance, while Alex Rigola is confirmed for Theater and Alberto Barbera for Cinema.

After 2015

In the recent years La Biennale nominated Alejandro Aravena and then Yvonne Farrel and Shelley Mc Namara for Architecture, Christine Macel and then Ralph Rugoff for Art, Antonio Latella for Theater, Ivan Fedele for Music and Marie Chouinard for Dance, while Alberto Barbera was confirmed for Cinema. For Architecture 2020 Hashim Sarkis was nominated.

Regarding the Film Festival, after suspending a project to build a new Palazzo del Cinema on the Lido, in 2010 a multi-year, general project to develop and modernize all the historical structures and cinemas was begun as part of a program to relaunch the world’s first international film festival. The following year, thanks to the updated structures and permanent locations, the festival assumed a new role and international prestige. The Biennale College Cinema (a unique formula among the various festivals) has obtained important results and recognition worldwide.

Paolo Baratta has always declared that the inspirational principles guiding the Biennale must be rigorous autonomy and a spirit of research, with the world’s esteem as its yardstick. Thanks to a consistent increase in its earnings, the institution’s level of autonomy is increasing.

In recent years, efforts have been concentrated on developing relations with local entities and creating educational activities: the “educational” program reaches tens of thousands of students and involves the intense participation of teachers. The International Kids’ Carnival and the Biennale Sessions project were created, encouraging structured visits from many universities around the world. And, lastly, the Biennale College, which offers educational activities aimed at new generations of artists, is gaining importance among the Biennale’s activities (in particular, DMT and Cinema a Archivio).

The constant work of renewal and growth within the organization has led to a high level of quality of the organizational structures, the personnel, and the internal procedures.

In 2015, he was called on to chair the selection committee of the candidates for State-run museums, following the reform of the state museum system.

He is president of the Accademia Filarmonica Romana.

He is a board member of the Fondazione Cini.

For many years, he was president of INARCH (National Architecture Institute).

Between 1988 and 2012, he was a board member and then president of the Fondazione Lorenzo Valla for Greek and Latin Classics, which he had supported as president of Crediop.

He was a board member of the Italian Institute of Historical Studies of Naples.

He was a board member of Ca’ Foscari University in Venice and LUISS in Rome.

He was vice-president of FAI (National Trust for Italy).

Honors

He is a Cavaliere di Gran Croce al Merito of the Italian Republic.

He is an Officier de la Legion d’Honneur.